Illustration by Katrin Friedmann

Hormonal contraception and your body

How does birth control work?

Top things to know:

Hormonal contraceptives are very effective at preventing unintended pregnancy

There are both positive and negative side effects from using hormonal birth control

Always consult with your healthcare provider, hormonal contraception is not a fit for everyone

Most American and European women will use at least one form of hormonal contraceptive, or birth control, at some point in their lives (1, 2). They are most likely to have tried the oral contraceptive pill (OCP) (1, 2) and about 2 in 10 American and European women are current OCP users (1–3).

Hormonal contraceptives are very effective at preventing unintended pregnancy (4). Between 0 to 9 in every 100 women and people with cycles relying on these will get pregnant over the course of a year, depending on which form of hormonal contraceptive they use (4). This number is lower in people who use hormonal contraceptives perfectly. In comparison, 18 in 100 people relying on male condoms will get pregnant over the course of a year (4). The implantable rod, called “the implant,” is the most effective form of hormonal contraceptive (4) and is usually placed in your arm by your healthcare provider. Less than 1 in 100 people using this method will get pregnant over the course of a year (4).

Although hormonal contraceptives are highly reliable for preventing pregnancy, between roughly 50-75% of American women who have used hormonal contraceptives have reported side effects that made them stop using them (1). Between roughly 2 to 4 in 10 hormonal contraceptive users from Western Europe have reported stopping due to side effects or worry over health effects (2).

If you choose to use a hormonal or non-hormonal contraceptive, it’s important to consider how effective, easy, beneficial, or harmful each method might be for you. Not every form of hormonal contraceptive works the same, so one may be a better choice for you than another. Non-hormonal birth control methods are another possibility for preventing unintended pregnancies. Both hormonal and non-hormonal forms of contraception have benefits and risks.

Using Clue to track your symptoms and side effects can help you when you discuss your options with your healthcare provider.

Biology of hormonal contraception

Methods of contraception can be classified as non-hormonal or hormonal. Non-hormonal forms of contraception, like condoms or the copper intrauterine device (IUD), don’t change the levels or functions of hormones within the body (4).

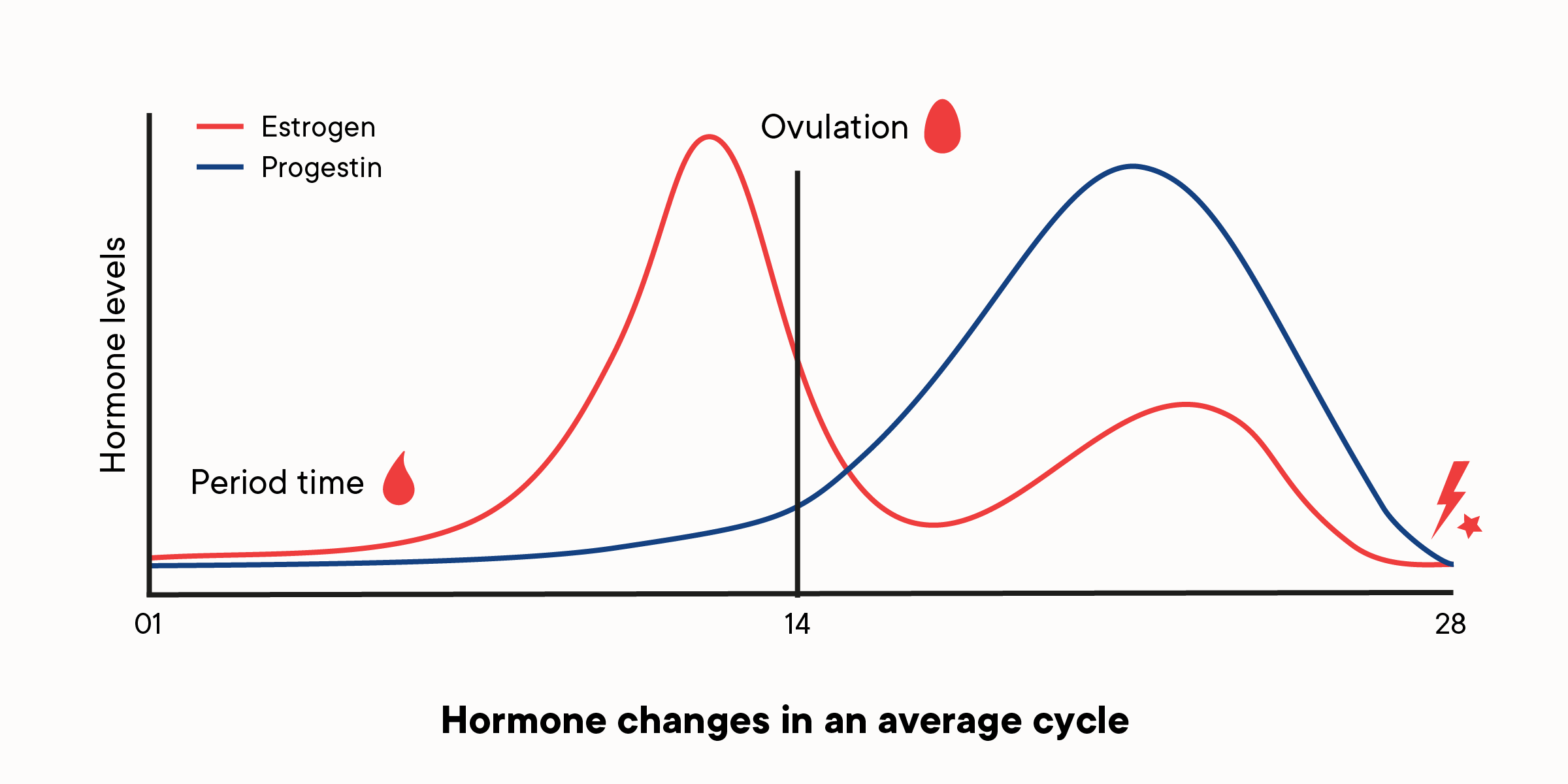

However, hormonal contraceptives change levels of estrogen and progesterone, as well as other hormones (4).

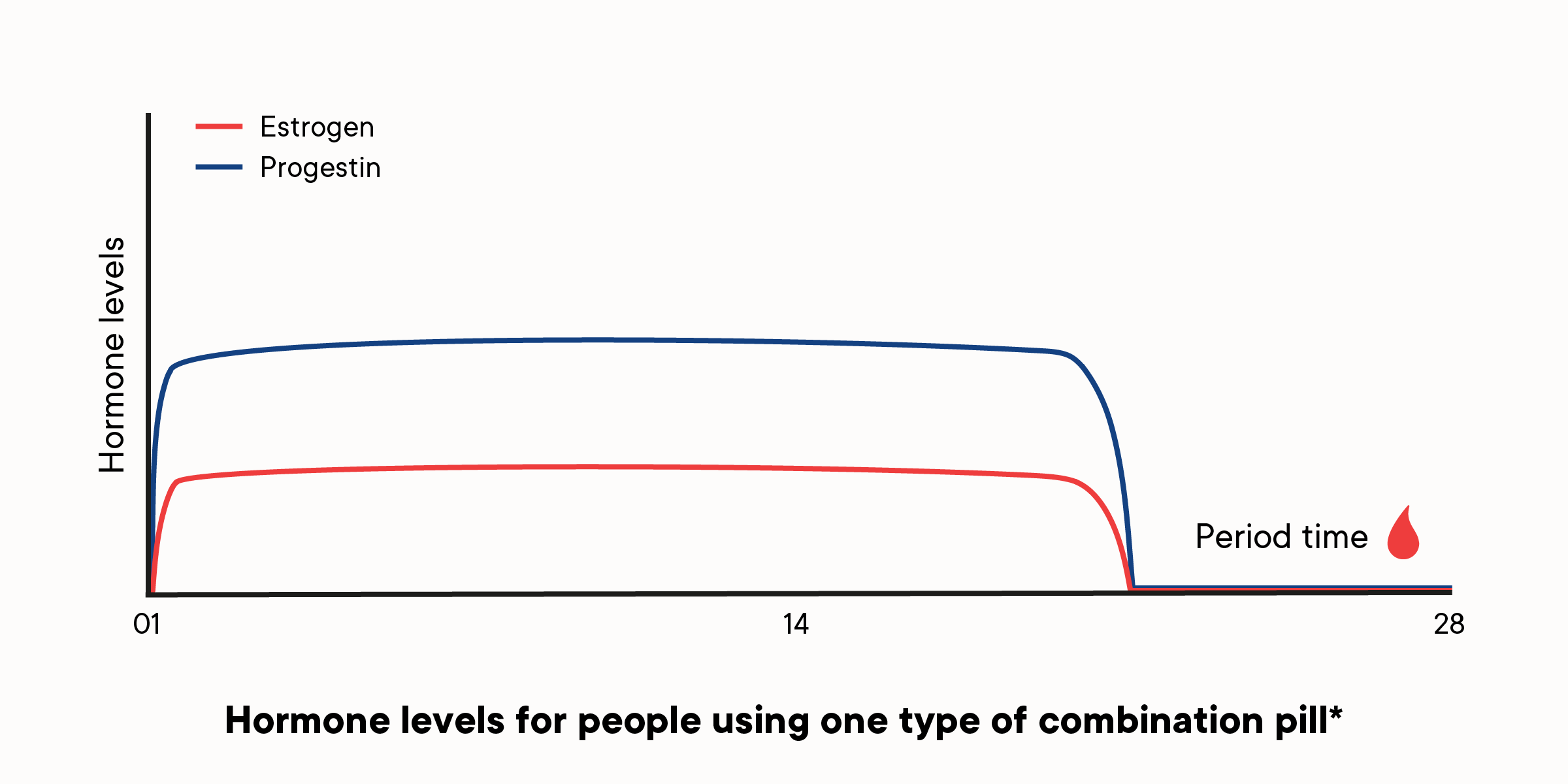

*This graph is based on one generic type of combined hormonal contraceptive pill across the cycle. In reality, hormone levels will go up and down as pills are taken on a daily basis, and different pills contain a different hormonal make-up

Hormonal contraceptives usually contain alternate forms of estrogen and the synthetic form of progesterone called progestin, or just progestin (3, 4).

People using the most common forms of hormonal contraception don’t ovulate. These methods stop the usual production patterns of reproductive hormones and prevent the ovaries from releasing eggs. They do this by stopping or changing the usual hormonal “cycling.” Exceptions include the “mini pill” and the levonorgestrel IUDs. These methods work in a different way, but still prevent ovulation in some people (5).

Hormonal contraceptives that include both estrogen and progestin are:

Combined oral contraceptives (COCs)

Hormonal vaginal rings

Contraceptive patch (4)

Hormonal contraceptives that include only progestin are:

Progestin-only pills (the “mini-pill”) (POCs)

Contraceptive shot or injection (typically under the brand name Depo-Provera)

Implantable contraceptive rods (“the implant”)

Levonorgestrel (LNG) IUD (4, 6)

Emergency contraception (“the morning after pill,” sometimes referred to by the brand name Plan B) also affects levels of estrogen and progesterone, either by increasing the amount of these hormones or interfering with proteins that interact with these hormones (4, 6, 7). Emergency contraception primarily works by blocking ovulation — it does not end a pregnancy after it has occurred (8). It’s not recommended for use as a primary method of birth control (4), but it is recommended in circumstances where contraception failed, contraception was used ineffectively, or no contraception was used for the prevention of pregnancy. Using emergency contraception as needed is safe and effective at preventing pregnancy if taken within 3–5 days, though it should be taken as soon as possible (9).

Physical side effects of birth control

Users of hormonal contraceptives report both positive and negative side effects.

Period bleeding is different when using most types of hormonal contraception, including COCs. The period changes from the typical shedding of the uterine lining, to a period-like bleeding, called withdrawal bleeding. Withdrawal bleeding happens in the week when pills contain no hormones, or in the time when a patch or vaginal ring is removed. Because withdrawal bleeding tends to be lighter than typical menstrual bleeding, hormonal contraceptives can reduce menstrual flow (10). People who experience heavy bleeding, prolonged bleeding, menstruation-related anemia or iron deficiency may benefit from hormonal contraceptives (10). These can also reduce painful menstruation, including pain caused by endometriosis (10).

"Menstrual regulation" is one of the top reasons people are prescribed hormonal contraceptives for reasons other than birth control (11). Doctors prescribe birth control to make bleeding more predictable, induce bleeding, or induce intentional amenorrhea (no bleeding at all) (11). This is sometimes the approach used for people with chronic reproductive conditions, like polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) (12). But hormonal contraception doesn't truly regulate periods, it delivers scheduled withdrawal bleeds. If the underlying cause of the unpredictable menstrual cycles isn't addressed, they will likely return after going off the hormonal method. This can contribute to delays in diagnosis and treatment.

Hormonal contraception can affect your skin. COCs can treat acne (10, 13), due to the acne-reducing effects of estrogen. Conversely, the development of acne, melasma, or negative changes to the appearance of skin are also common side effects of hormonal contraception (14, 15). These negative effects seem to be most strongly related to POCs, so switching to COCs or other forms of combined hormonal contraceptives may help address these concerns.

Nausea, headaches, and breast tenderness are also commonly reported side effects (14, 16), though there is evidence to suggest these side effects are strongest in new users and diminish over time (14, 17). Hormonal contraceptives may also reduce breast tenderness with long term use (14).

Weight gain and changes to libido (sex drive) are concerns for many people taking hormonal contraceptives (14, 16). Other than the contraceptive shot, which has been found to increase weight in users (14), most research suggests the average hormonal contraceptive user experiences little or no change (14). Some people might notice their libido is higher or lower overall, though many people report no change (18). Hormonal fluctuations in a” cycle not influenced by hormonal contraception also tend to create times of higher and lower libido (a higher sex drive is common leading up to and around the time of ovulation) — the hormonal suppression that happens with most hormonal contraceptives mean these peaks and valleys will go away, or change (19).

If you experience uncomfortable side effects from your hormonal contraceptive, talk to your health care provider. They may recommend switching to a contraception with a different combination of ingredients.

Emotional side effects of birth control

Hormones impact brain function. Special proteins on cells respond to specific chemicals for progesterone and estrogen. These receptors are found in many regions of the brain., including the amygdala, which regulates aggression and fear, and the hippocampus, which has important functions for memory processing and storage (20).

Progesterone and progestin indirectly reduce the amount of serotonin, an important mood-regulating neurotransmitter, in the brain (21). Theoretically, progestin from hormonal contraception may cause mood changes in users, (21), but it just isn’t easy to prove whether hormonal contraceptives cause mood changes.

The relationship between hormonal contraceptives and depression (21, 22) has been a major area of research. In one recent study of over one million Danish women aged 15 to 34, researchers found women using hormonal contraceptives were more likely to be prescribed an antidepressant or be diagnosed with depression than women not using hormonal contraception (21). Women using the contraceptive patch were twice as likely to be prescribed an antidepressant as compared to women not using hormonal contraception, while women taking POCs were 1.34 times more likely (21). The risk for women taking COCs was lower than that of POCs, but still significantly higher than non-users of hormonal contraception (21).

Despite this strong evidence, the relationship between depression and hormonal contraception is not clear cut, and is likely different for different people. And even in the case of an increased risk, the overall risk may still be very small.

For people with premenstrual syndrome (PMS), premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) or major depressive disorder (MDD), hormonal contraception, particularly OCPs, may cause positive changes to their mood (10, 22).

Birth control and cancer

People using OCPs have no change in risk (and may have a decreased risk) of fibroids, colorectal cancer, ovarian cancer, and endometrial cancer (10). In contrast, OCP use has been linked to the development of breast cancer (10, 23). People who have used OCPs for many years may be at an increased risk for breast cancer, whereas short-term use seems to have no effect on breast cancer risk (10, 23). Research on this topic is mixed. Different formulations of OCs may have different effects on breast cancer risk and certain groups of people, such as those with a family history of breast cancer, may be at an increased risk in comparison with those without such a history (10, 23, 24).

Cardiovascular birth control side effects:

Using hormonal contraceptives comes with the potential of serious cardiovascular side effects (3, 14, 25–30), though such complications are rare.

Hormonal contraceptive use is also associated with changes to metabolic function. COC use is linked to changes in the levels of amino acids, fatty acids (lipids), vitamin D, inflammation markers, and insulin in the body (3), in addition to changing the levels of estrogen and progesterone in your body. Some of these changes, such as to inflammation markers, are linked with the development of cardiovascular disease (CVD) or stroke (3). These changes seem to disappear after cessation of OCP use (3).

Conversely, POCs do not seem to have a relationship with metabolic processes (3), which suggests that these changes are associated with estrogen or that progestin needs estrogen to create changes in the body.

People who take hormonal contraceptives are at increased risk of blood clots, medically referred to as thromboses, particularly in their veins (25–28). This risk may be modified by the type of estrogen and the amount of progestin (25). Strokes and heart attacks are related to the increased risk of blood clots, as both ischemic and thrombotic strokes are more likely to occur in OC users than non-OC users (29, 30).

Despite increased risks, the likelihood of developing a serious medical problem from typical use of hormonal contraception is low. You can be at an increased risk but still have a low risk.

For example, the maximum risk of blood clots in OCP users is estimated to be about 9 to 11 clots in 10,000 years, depending on the ingredients in the OCP (27). While this risk is 2 to 10 times higher than that of non-OC users, the risk of developing blood clots in postpartum women in the three months following delivery is four times higher than the risk in women taking OCPs (27).

There are risk factors that can increase the likelihood of developing a serious side effect from hormonal contraception. People who are obese, smoke, are older than 35 years old, or have vitamin deficiencies are at an increased risk (26,27). Additionally, some people who have PCOS along with other metabolic risk factors may also be at increased risk (12,31). If you are unsure whether you are at a higher risk for the development of cardiovascular disease or blood clots while using hormonal contraception, talk to your healthcare provider.

Hormonal birth control can have both negative and positive side effects

For many people, hormonal contraception is safe and effective at preventing pregnancy with minimal-to-no side effects. Many people may also experience positive side effects from hormonal contraceptives, and sometimes these positive side effects are the primary reason they take birth control.

Other people may find hormonal contraception is not a good fit for them. If you feel that your hormonal contraception may pose a risk to your health or is causing negative side effects or depression, talk to your healthcare provider. Because not all hormonal contraception has the same amount of estrogen or progestin, it is possible that you will be happier using one type or brand more than another.

Similarly, although there is thought to be no difference between the active ingredients in generic and brand name hormonal contraceptives, it is possible you may respond differently to a generic or brand name due to the inactive ingredients and so healthcare providers still recommend prescribing based on the preference of the user (32).

You are your best advocate for your health, so it is important to be honest and clear with your needs, be they pregnancy prevention or the management of other concerns. Your needs may be best met by using hormonal contraception, but it may also be the case that the risks do not outweigh the benefits for you.

Article originally published January 6, 2017.