A podcast about how hormones shape our world.

Latest episode:

Who you gonna call? Mythbusters!

About Hormonal

Hormones affect everyone and everything: from skin to stress to sports.

But for most of us, they're still a mystery.

Even the way we talk about hormones makes no sense. ("She's hormonal.")

So let's clear some things up. Each week, Rhea Ramjohn is asking scientists, doctors, and experts to break it all down for us.

Subscribe on your favorite platform:

Episodes

- Season 1

- Season 2

Episode 0

August 25, 2020

A Sneak Peek at Season 2

As we work hard on Season 2 of the Hormonal podcast, we’re dropping into your feed with a special request, and a small behind the...

5 min

Episode 1

October 11, 2020

Hot or not? Birth control & sex drive

How birth control affects your sexual desire, self image, and weight fluctuations.

25 min

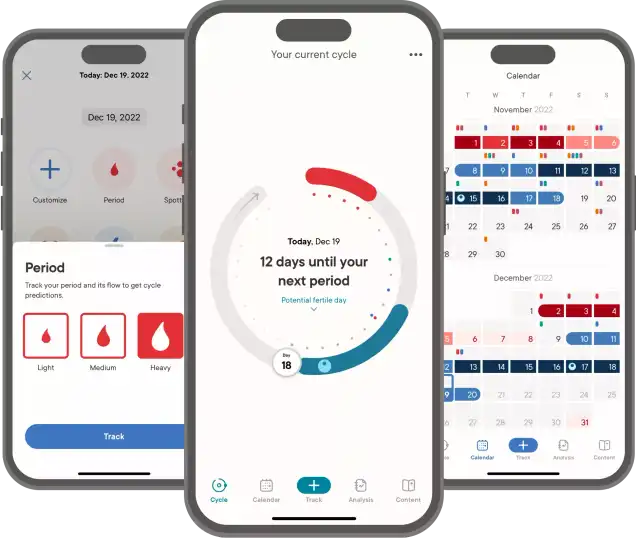

Support Hormonal & the period tracker that’s different from the rest.

Subscribe to Clue Plus

Episode 2

October 19, 2020

The ABC: Abortion & Birth Control

What’s it like to get an abortion and the surprising ways the pandemic is changing abortion access.

34 min

Episode 3

October 26, 2020

The many sides of side effects

Hormonal birth control: positive, negative, and neutral effects

33 min

Support Hormonal & the period tracker that’s different from the rest.

Subscribe to Clue Plus

Reproductive choice and reproductive justice

with Dr. Loretta Ross

Episode 4

November 2, 2020

Reproductive choice and reproductive justice

Accessing birth control against the odds

35 min

Episode 5

November 9, 2020

Happy birthday, birth control

Controversy and celebration on the 60th anniversary of the pill

42 min

Episode 7

November 23, 2020

Risky business: birth control during COVID-19

COVID-19 is changing how we access birth control

30 min

Support Hormonal & the period tracker that’s different from the rest.

Subscribe to Clue Plus

Who you gonna call? Mythbusters!

with Lynae Brayboy, Amanda Shea & Hajnalka Hejja

Episode 8

November 30, 2020

Who you gonna call? Mythbusters!

Clue’s Science Team busts your birth control myths

37 min

Credits

Season 2

Executive Producer: Kassandra Sundt

Host: Rhea Ramjohn

Editorial Help from: Amanda Shea, Steph Liao, Nicole Leeds

Clue Design: Marta Pucci & B.J. Scheckenbach

Web Team: Yomi Eluwande, Jane Parr-Burman, Maddie Sheesley

Special Thanks: Trudie Carter, Ryan Duncan, Aubrey Bryan,

Claudia Taylor, Léna Calvarin, Lynae Brayboy

Mixing and recording help from: Bose Park Productions & Rekorder Studios in Berlin.

About Clue

Clue is a period tracking app that uses data and science to help women and people wih cycles to understand their bodies. It's also a menstrual and reproductive health encyclopedia.

Learn more about the Clue app and check out what Clue is doing to advance menstrual health research.

Rhea Ramjohn,

host of the Hormonal Podcast

Rhea Ramjohn,

host of the Hormonal Podcast

Your Host

The more knowledge we have about our hormones, our medical & menstrual care, and our reproductive rights, the more we empower ourselves and one another.

Hormonal has offered me the true privilege of speaking with people who have the expertise on the scientific knowledge about our hormones and cycles, as well as those sharing their lived experiences, caring for people with menstruation and how, all combined, shapes our lives everyday.

Gathering facts as well as personal stories are so vital to our understanding of our health, our his/herstories, and our cultures. I deem it a privilege because we haven't had many platforms nor opportunities for menstrual health information being broadly accessible.

Episode 2

PMS is real. PMS isn’t real.

PMS is real. PMS isn’t real.

PMS is not just in your body, or in your head. Our premenstrual experience is influenced by culture, and the world around us.

About

Fact: Right before your period, your hormones and body can change. Myth: you’re automatically going to turn into a weepy, emotional, and irrational B*TCH.

So how do the cultural perceptions around Premenstrual Syndrome (PMS) change how you experience that time of the month? Turns out, a lot.

For more on this research we’re joined this week by Jane Ussher. Jane is a professor of women’s health psychology at Western Sydney University. She’s also the author of “The Madness of Women: Myth and Experience”.

Transcript

This transcript and interview were edited for clarity.

Content Warning: In describing one woman’s experience with an unsupportive partner, our guest quotes a story where derogatory terms for a mental disorder were used against a research subject.

Rhea Ramjohn: Hi, it’s Rhea Ramjohn and you’re listening to Hormonal, brought to you by Clue. Clue is the period tracking app and menstrual encyclopedia -- where you can find the answers to questions like, what does the color of my period blood actually mean?

Do you ever get the feeling that the changes that you feel around the time that your period comes is totally in your head? Or are you firmly convinced that these hormones are raging inside your body, as your uterus prepares to slough off its lining, and there’s not a dang thing you can do about it?

Well our next guest says both are true — that hormonal changes before your period are real. But how you interpret and experience the changes are based on more than just your period—it has to do with culture, and what's happening in your day to day life.

In other words: PMS is not just in your body, or in your head. How we experience it is based on the world around us.

And, as our next guest will tell you, even though millions of people experience PMS every month, scientists do not know much about it.

Joining us now to explore these issues and more is Jane Ussher. Jane is a professor of women’s health psychology at Western Sydney University and she joins us on the line from Sydney.

Jane, thanks for joining us on Hormonal.

Jane Ussher: Pleasure.

Rhea: Let's get started with explaining a PMS a bit. Can you tell us about the kinds of symptoms someone might experience and the spectrum of severity?

Jane: Well, having some sort of changes across the menstrual cycle is completely normal. So, about 95% of women will have some sort of change. So for some women it's negative, so it might be increased irritability. It might be feeling a bit more sad. Some women feel differently about their bodies, they feel more negatively about their bodies. But other women actually feel more energetic, more creative, more sexual. So, there's a whole spectrum of different changes.

For the majority of women it's not a big issue. And women can live with those changes. Some women don't even notice them. But there's a smaller proportion of women, up to around 30%, that might have moderate changes in some months, moderate-negative changes. And it's a very small proportion of women about 5%, who have severe changes that have a really big impact on their lives. And that's primarily the psychological symptoms. So feeling anxious, feeling depressed, feeling that you really can't face the world.

Rhea: And you said about 5% of women experience was that PMS or PME?

Jane: PMDD. OK.

Rhea: PMDD, sorry.

Jane: So I've been doing research on the menstrual cycle and on PMS for over 30 years now, and I'd normally talk about “premenstrual change,” to say these are changes that happen and then normal. PMS is a shorthand for "premenstrual syndrome." And that implies there's something wrong. It's a pathology. It's a diagnosis. And that's really the moderate symptoms which affect up to 30% of women. The most severe symptoms are described as Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder (PMDD). And that's a term that's actually appeared in the DSM, which is the American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic Manual, and that's defined as a psychiatric disorder, it was actually included in that in the DSM in 2013. So that's a very small proportion.

But we need to think about this on a continuum, so if you think most women get some change, about 30% of women. In some months, it's moderate change that might be difficult and a very small proportion of women at the end of the continuum, it's severe change that really needs help and treatment.

Rhea: And to clarify for our listeners what would you say would be the defining line between a diagnosis for PMS and one for PMDD?

Jane: So, it's severity. So if you feel that you can't cope. If you feel you're really out of control. If you feel that you can't face work, you can't face relationships, you might be having suicidal thoughts. That's really on the severe end of the continuum. But if you're just feeling mildly irritated with your partner or with your children or your colleagues at work, that's pretty normal. And it's actually looking at things that you can do in your life to help you cope with that to alleviate stress, to alleviate [the] burden. You'd want to do that across the board, but then in the more normal group, you don't really need to think about medication or anything that's that's going to have a really big sort of medical impact on your body. You're thinking about it normally in terms of, “Okay. I'm feeling a bit more uptight at this time of the month, perhaps I don't take on so much at work, or ask my partner for help or take a bit more time out.” And that generally works for women.

Rhea: OK, so let's try to understand PMS and the cycle a little bit more in detail. Some of these symptoms come from the hormonal changes. So can you break that down for us, how does the change in hormone levels trigger the symptoms of PMS and PMDD?

Jane: Well, that's really the million dollar question. We don't completely know the answer to that. And I think some people have argued that if men had PMS, we would have worked out what was happening from a biomedical perspective many decades, if not centuries, ago and we would have a very good and simple with no side effects cure for it.

Rhea: Right.

Jane: We don't really know and there's many, many different theories so some people say that it's changes in progesterone, some say that it’s changes in estrogen. Other people say it's to do with neurotransmitters particularly serotonin. The answer is we really don't know.

And there's been many, many different forms of medical treatments used, primarily the oral-contraceptive pill in terms of giving women either estrogen or progesterone or combination. Or SSR, so anti-depressants. Prozac being the most common brand name.

Now, what people have often argued is that these treatments work for some women, they don't work for all women, so therefore that's demonstrating that is either an absence of progesterone or an absence of serotonin that's the problem. But if you take a different sort of analogy, if you've got a headache and you take some paracetamol or some aspirin, and it works, that doesn't mean it's an absence of paracetamol or an absence of aspirin that's actually causing the headache. So, often causal interpretations have been made about premenstrual distress on the basis of interventions that can seem to have some effect.

The truth is we really don't know. And what I would say is that we know that there are hormonal and physiological changes happening in a woman's body across the menstrual cycle, so there are hormonal changes, there are potentially changes in neurotransmitters. There's also changes in physiological arousal, so in autonomic arousal, so women can feel more “on edge,” but they can also feel more excited, they can feel more sexual. And those changes actually interact with what's happening in a woman's life.

So, if you're under a lot of stress, if you're under a lot of pressure, if you've got lots of difficulties in your relationship, you’re juggling work and life and children and trying to have a social life, trying to stay slim, you know, a lot of the pressures that any woman's under -- that actually can be more acute and can actually make you feel more sensitive, more vulnerable in the premenstrual phase of the cycle. And then what you think about those changes also has an impact. So if you think, "Oh, I can't cope. Oh, I'm crap. Oh, I'm fat," because you feel a bit bloated, that makes you feel worse. So it's a vicious cycle. So, what we need to look at is the biological factors what's happening in the body alongside a woman's environment and alongside what she's thinking about what's happening to her. And that's where we can help women in non-pharmacological ways, by unpicking some of that cycle.

Rhea: Now, I find that really interesting because you've also written that PMS is a Western cultural concept. So keeping in mind that women experience PMS very differently across the world or that they may report on experiencing PMS differently across the world, can you explain for our Hormonal listeners, how this actually works or how you found this out?

Jane: Well, if you take a step back, what we know is that symptoms and illnesses are always culturally located. So, if you go to different cultures, different points in history, we have different, what people describe as symptom complexes. What we see as legitimate illnesses and ways that we actually report distress.

So, if you go back to PMS and reproduction, in the 19th century there was no concept of PMS. In fact it was first discussed in 1931, in North America. And in the 19th century, women reported "hysteria," and then “neurasthenia.” And these were "disorders," I put inverted commas, that were often associated with the reproductive system. You know, we can go back as far as Plato and Hypocrates and they believed in the wandering womb, and that was seen as the problem in women's bodies.

In 1931, [Robert] Frank, who was a medical doctor and also Karen Horney, who was a psychoanalyst, first described this notion of what they talked about as premenstrual tension, PMT. And they actually said it was to do with hormones, to do with estrogen. And PMS was first described in 1956 by Katrina Dalton who is a British gynecologist.

Now, these notions that women would have psychological disturbance in the premenstrual phase of the cycle were happening in the U.K. and in the U.S. They really had very little impact in other parts of the world. And you really see this legacy today. Whereas in the U.S., the U.K., and in Australia, we've taken up this pathologizing discourse, as I would call it, around the menstrual cycle and around the premenstrual phase of the cycle. And we expect women to be mad or bad or dangerous premenstrually. And women take that up, in hundreds of thousands and actually feel irritable, feel angry, and then blame it on them, on their bodies on the menstrual cycles.

Now what we know in terms of other cultural contexts, if we say to women: “Do you experience those sorts of changes across the cycle?” women don't report them. They may report some physical changes, so they may report feelings of bloating or sometimes menstrual pain. But that usually is when the period starts. But they don't tend to report premenstrual symptoms, particularly in Asian cultures. And what we also know is that when women come from cultures where there isn't a discourse around PMS and they move to the U.K. or the U.S., then they start to report it.

So the argument is that it's a culture bound syndrome. It's both a gendered syndrome, because it's a way of attributing women's anger and distress to their bodies, but it's also a culture bound syndrome because it's been created by Western, particularly North American and British culture and then women take that up.

Now what's interesting about it is that women actually experience anger, depression, distress, classic symptoms of PMS and PMDD across the whole cycle. But what we know is that when they're premenstrual, they'll attribute it to their bodies but when they're [at] other times of the cycle they’ll attribute it to other things in their life. So they might say, "Oh it's my partner or I'm late for work or you know it's Monday morning and I'm feeling lousy." So even within Western culture, we can see the way women are actually inculcated in what some might say in a negative discourse around menstruation.

Rhea: That's the part of your research that I find most interesting, that you find that people who menstruate, their symptoms or their changes are not strictly hormonal. Could you tell me a little bit more about what you mean by that?

Jane: Well, it's not simply a hormonal cause for any negative experiences that people who menstruate might have in the premenstrual phase of the cycle.

So, I've been involved in developing psychological support for women who experience moderate to severe PMS and PMDD. And we've developed a form of therapy, psychological therapy, that we've evaluated both on a one-to-one basis as a self-help therapy and as a couple therapy. And what we've found is, we've interviewed hundreds and hundreds of women as part of these evaluations, and often I say to women, you know, “Tell me about your PMS.” And the first thing they usually talk about is an argument or something that's happened with their partner or with their children, sometimes at work as well, but, generally women control it at work.

So what's happening is there's a trigger. There's an environmental trigger that's happening and I'll just give you a classic example from one of our interviewees. But this is a really typical example of PMS. I said to a woman in one interview, “Tell me about your PMS.” Now, she didn't talk about hormones, her body, what was happening inside. She said, "Well, I was standing at the kitchen sink and I was doing the dishes, and I had the dinner on the stove for the two children and the children were arguing, and I was trying to get them to do their homework and I was looking out in the garden and my husband was sitting there having a beer.” And that was her PMS. She was feeling really, really angry with her partner and she yelled at him something. And then she felt really bad about herself and she said, “That's just typical PMS to me.”

Now, I would say that that's actually more about what's going on between her and her partner than what's happening hormonally in her body. And it might be that in the premenstrual phase of the cycle, she's less likely to self silence and more likely to be cranky with him. But actually, what's useful to do is take a step back and think, well maybe, she shouldn't be doing all of those things while someone else who lives in the houses is having a nice time, having a beer. Maybe it's about asking for support. Maybe it's again about getting her partner on board. And in fact what we found is in relationships where women have that support, where they can say, “Look I'm feeling a bit irritable today,” or “I feel like a bit need a bit more help today, or “Can you take the kids today?” they're less likely to experience premenstrual distress. So it's certainly not just hormonal.

[Sponsor Break]

Announcer: Hormonal is brought to you by Clue. The period tracking app, and menstrual health resource, that takes all parts of your cycle seriously.

Jesse: Well, I think a lot of Clue users don't realize that the website is basically an encyclopedia.

Announcer: That’s Jesse. He’s an engineer who works on the website. He says anything you can track on the app, you can also read about online.

Jesse: The really important work that we're doing on the website is getting accurate, reliable, and empathetic health information out to people for free. And it's really cool, it’s really important work. And I think part of why it's so important is that there are a lot of websites that provide sort of related information but it's often very clinical sounding and a bit intimidating. And so this is all written from a point of view of empathy and care, but it's also scientifically backed.

Announcer: To support the science-backed app and website that you know and love, subscribe to Clue Plus. It funds the work here at Clue, the period tracking app that doesn't sell your data, doesn't show you a bunch of ads, and was founded and is led by women.

For more -- check out Clue.Plus.

Alright, back to the show.

[End of Sponsor Break]

Rhea: Right. I can completely understand that because actually once I got into a long term relationship in my early 20s, it was the first time I actually felt comfortable enough to start talking to my romantic partner and saying listen, "I'm not having a very good time this week. It's time for you to just like give me some alone space, alone time, where I can just indulge in my own, in myself.” Basically. And it began this sort of journey of like self care and taking time out.

So, instead of looking at this one week every month as this really terrible thing that's about to happen to me, I started to turn that narrative around a little bit and make sure I let the people closest to me in my life know, "Listen this week it's all about me taking care of myself." So I know, like I've done that for myself and it's been really helpful.

I was wondering if you could tell our listeners how their partner, or how the close people in their lives, in their families, can actually help or affect the way that they experience any type of menstrual change.

Jane: Well. I think the key to it is communication. And you've given a really good example from your own life.

So a number of things. I think the first thing, as a woman yourself, to be aware of what's happening. So if there are particular times where you feel more vulnerable, you feel like you do need more space, and actually when I talk to women and I say, "What's this thing you do to cope with PMS?” They say, “I go under the dune or under the duvet," or you know just the classic -- you know Virginia Woolf talked about “a room of one's own.” And it doesn't have to be literally a room, it can be some space that can be going for a walk, going in the bath, just saying you know I just need some me time. And even if that's only for half an hour that's really important for women. So having an awareness of the changes in our bodies, those changes may not happen in the premenstrual phase of the cycle, some women actually feel distressed in the luteal phase.

Some people, some women feel very distressed during the menstrual phase when they're bleeding and actually if you track your cycle then you can see when you’re actually up and when you're down and actually understand your own pattern. So awareness is really important. The second thing is actually communicating with your partner or partners if you have more than one partner or it might be if you're living with friends or living with family, what you need and when.

So I say one of the things is don't let things build up until that premenstrual phase where you're actually going to blow a gasket and get really angry. Talk about things you're not happy with at other times when you might be feeling a little bit more calm. Actually say, “Look. I'm not happy with the fact that you don't ever help with the kids” or, “I'm not happy with the fact that you always leave your towel on the floor.” Those are very stereotypical examples I'm coming out with here. Or, “I'm not happy with the fact you don't listen to me when I'm trying to tell you something,” and actually see if you can work that out at other times in the cycle.

But if you are feeling vulnerable and everything's too much, it's actually about kind of saying what you want: Can I have a cuddle? Can you leave me alone? Can I have some space? Can we go out and party? You know actually communicate that to your partner.

Now what we can't guarante is that your partner is going to listen and we've done research in both heterosexual and lesbian relationships and we found that some men are incredibly supportive but men are actually less likely to be supportive of women. We could say it's because they don't empathize. They don't understand. Whereas if you've got a woman partner, she's more likely to go through some sort of changes herself so she's more likely to understand.

It's also we know in lesbian relationships, they tend to be more egalitarian. So women are more likely to be sharing things in the house. But that's the case also in a lot of heterosexual relationships today. So, I think women need, if your partner is a man, then you need to explain what's happening. Help the men to understand. That can actually then get the partner on board for support.

Rhea: Right. So tell me a little bit more about the study that you wrote about where you found that people in lesbian identified relationships actually report having less severe PMS. Could you tell us some more about that?

Jane: Well, what we found was that women in heterosexual and lesbian relationships experience premenstrual change across the board. So it's not that lesbians are immune to PMS so they might have the same sort of symptoms they might feel irritable, they might feel distressed, they might feel more vulnerable. But it's actually what happens in terms of the spiraling.

What we found is in heterosexual relationships for some women, the partners would provoke them when they were premenstrual, so they would pick a fight. They would insult them said one woman talk to us about her partner saying, "Are you schizo Elaine? Or Mad Elaine? or Bitchy Elaine? What have I got today?" Which actually made her feel really distressed. The often male partners would avoid women, just saying, "I can't be with you when you're like this," would be very blaming and quite negative. And in fact there's a whole website, where men talk about the terrible experience they have of living with premenstrual women. And so that can actually, that sort of ties into a general cultural stereotypes about, you know, “mad premenstrual women,” and how they, really what I've called the “monstrous feminine incarnate.”

So, that was much more common in heterosexual relationships. And what we found in lesbian relationships is the partners, there was no examples of partners doing this pathologizing, of making women feel mad, making them feel worse. So, a woman might be irritable with her partner. But, the partner was much more likely to say, "Look. I think you need a bit of space and I'll help you out do you want to have a bath? Can I make dinner tonight?” And actually to be able to empathize with the experience. And also that women were less likely to get to that peak of anger and irritability, because they were getting more support at home and that is a real key to to women's premenstrual distress, is that sense of over responsibility of having to do everything never having time for themselves.

And so in the lesbian relationships, women were more likely to have that support, so less likely to get to that kind of extreme of distress. So, I think that's what's really important to be able to both communicate about changes and about what you need but also to look at general issues in a relationship that might be causing distress. And having unequal distribution of labor is a really big cause of anger in many, many women's lives.

You know, I've heard it said that men complain that they want more sex and women complain that they want men doing more housework. And actually if men did a bit more housework with the women partners, maybe there'd be less anger in the relationship and more sex, so there'd be a bit, everybody would be happy all round.

Rhea: That would be a dream. I'm just thinking about the lesbian identifying couples where that partner’s also leaving their towel on the bathroom floor. I think that that could probably lead to a spiral as well.

Jane: And if you’ve got both women who are premenstrual at the same time… So, I'm certainly not saying there's a lesbian utopia out there and that women in lesbian relationships don't have fights because I certainly do. But I think having empathy can help.

Rhea: All right. So communication for sure. You said tracking your cycle -- so of course being aware of which parts of a person's cycle or your own cycle that you may feel or have characteristic traits of feeling a certain way. I know that that has really helped me, tracking, the communication, as you said before. And then of course the empathy and having let's say a more egalitarian relationship.

So what would be, let's say your prescription, beyond those four tips for the folks or for the cultures, that are struggling with premenstrual syndrome or menstrual changes?

Jane: Well, I think the first thing is keeping a diary so that you know what's happening, so you learn your own body and you learn your own cycle. And we know that that's actually one of the best ways of reducing PMS, and in fact, it's a frustration for many PMS researchers because women say, "Oh I get terrible PMS,” and then you have to get them to keep a diary for three months and it can kill the PMS. So, it can be as simple as that.

The second thing is actually looking at, in part of your diary look at, what other things are happening in your life, when you have days that are bad. So, look at the triggers and that can help you see whether it's things at home, whether it's things at work. Keep a diary of your feelings as well, so what sort of things are you saying to yourself? What sort of thoughts are you having? And are you having very negative self thoughts, and you can challenge those so if you think, "Oh, I can't cope, I feel terrible, I'm awful, I'm ugly" and they're things that women often say or women experience severe premenstrual distress or moderate pre-menstrual distress. So challenge those thoughts. Look for alternative evidence. Rather than thinking, “I can't cope," just thinking, "Well, I need an easier day today. I've got too much on." And legitimate taking time for yourself.

So, it's the other thing leading to that is about self care and coping and you've already talked about [yourself] in terms of your own life. But it's actually one of the things we do when we work with women therapeutically is we say to them: “Think about some things you enjoy doing and actually make sure you do at least one of those things every day.” And a lot of women surprisingly don't do anything that they enjoy. Particularly, if they've got children and they're working and there’s just no space in their lives for things that they enjoy. Actually taking things time for things you enjoy even if it's just half an hour a day, actually having some space away from responsibility, so that sort of self care that we need to do, looking after ourselves physically and psychologically.

And it's about not feeling as if you're going mad. Some of the women we've talked to say, "Look I think people say it's all in your mind, it doesn't exist. I feel like I'm going mad." Actually thinking, No, there are some changes happening in our bodies, but what's happening in our lives and what we think about them, all combines together to result in this PMS or Premenstrual distress.

And we can intervene by looking at challenging our negative thoughts and looking at what's happening in our environment. And that will significantly reduce the premenstrual distress.

Rhea: Are there cultures who view premenstrual change as a sort of superpower or being super charged, a supercharged time of the month?

Jane: Well, in some cultures, menstruation is just seen as a normal part of life. And the premenstrual phase is just accepted as a normal part of life. But what we see with some women, if you ask them the question about positive premenstrual change, or do you get any positive experiences? What you find is that some women will talk about having much higher libido, that it is a time when women really want to have sex.

It's also for some women, for example who are athletes, they can feel that they've got much more energy. Women who are writers can feel much more creative. Artists feel much more creative. I know myself, at times, when I was premenstrual, I often found it was the best time to write and when I was writing books, I'd often have an incredibly creative time.

If we think about it as an increased energy, it can actually be channeled positively, as well as negatively. And we have a sort of cultural context where we expect it to be seen as anger, as irritability. But women can actually turn that around and actually channel it really positively.

I think it's really interesting, also, to look at menstrual art. There's been a resurgence in menstrual art, which sort of reflects those sorts of ideas, where we're in a way, it's a counter narrative to this seeing as menstruation and the premenstrual phase as a sign of a monstrous, is actually celebrating the power of menstruation the power of that premenstrual energy. And I think that's something that women can tap into and certainly enjoy.

Rhea: I also found in reading your research and reading your articles, you found that women in Asia and Latin America tended to report that they did not have some sort of premenstrual change. Do you have any idea why that may be?

Jane: Well there's different arguments for it. What I would say is that we don't have that notion within particular cultures that the premenstrual phase is a sign of illness. So women are not then, if they feel any psychological changes at that time, they're not attributing it to their bodies. So that they don't have an expectation that they will have any psychological symptoms. And so that's, I would say, that's the primary reason why. It's not that women in Latin America countries or Asian countries have anything different happening physiologically. It's just that there's not that whole expectation that they will experience premenstrual change.

Now, some people could say that means, “Oh my God, they've got PMS and there's just no legitimate syndrome.” And there maybe a little bit of that. We've done some research here in Australia, where we've interviewed women from migrant and refugee backgrounds and we asked them about PMS and premenstrual change, and they all laugh about it, and they say, "Oh no. There isn't such a thing," they don't have it.

But then when we say to them, "Do you ever feel more irritable at that time?" And some women will say, "Oh yeah, when I think about it, I do sometimes. But it's not a big deal." And they think it's kind of ridiculous that you'd give it a label and that you'd certainly want treatment for it.

So it may be that there's some change in women's experience but they're not, they're not seeing it is a really negative thing. It's not a really big deal. And they certainly don't either self diagnose or feel that they need a diagnostic label for it. Now, there may be some women in those cultures who do get severe changes and we don't understand why some women are at the end of the continuum with the severe changes and in those cultures, those women may not be getting the help that they need. So that's a downside of not having this cultural discourse around PMS.

Rhea: Jane, this has been a fascinating conversation. Thank you so much for joining us.

Jane: It's been a pleasure.

Rhea: Jane Ussher is a professor of Women's Health Psychology at Western Sydney University. You can read more of her work in her book: "The Madness of Women: Myth and Experience.”

Hormonal is brought to you by Clue. If you like the podcast, subscribe and rate us five stars on your platform of choice. Or find us on social media!

To support the work here at Clue -- subscribe to Clue Plus. Every cent goes towards informing you -- that includes the app and the archives of meticulous menstrual health information on the website. Including the answers to the question at the top of the show. Check the links in the show notes for more.

You can find out more about Clue Plus at Clue.Plus.

Episode 2

October 7, 2019

PMS is real. PMS isn’t real.

PMS is not just in your body, or in your head. Our premenstrual experience is influenced by culture, and the world around us.

About

Fact: Right before your period, your hormones and body can change. Myth: you’re automatically going to turn into a weepy, emotional, and irrational B*TCH.

So how do the cultural perceptions around Premenstrual Syndrome (PMS) change how you experience that time of the month? Turns out, a lot.

For more on this research we’re joined this week by Jane Ussher. Jane is a professor of women’s health psychology at Western Sydney University. She’s also the author of “The Madness of Women: Myth and Experience”.

"if men had PMS, we would have worked out what was happening from a biomedical perspective many decades, if not centuries, ago and we would have a very good and simple with no side effects cure for it."

Transcript

This transcript and interview were edited for clarity.

Content Warning: In describing one woman’s experience with an unsupportive partner, our guest quotes a story where derogatory terms for a mental disorder were used against a research subject.

Rhea Ramjohn: Hi, it’s Rhea Ramjohn and you’re listening to Hormonal, brought to you by Clue. Clue is the period tracking app and menstrual encyclopedia -- where you can find the answers to questions like, what does the color of my period blood actually mean?

Do you ever get the feeling that the changes that you feel around the time that your period comes is totally in your head? Or are you firmly convinced that these hormones are raging inside your body, as your uterus prepares to slough off its lining, and there’s not a dang thing you can do about it?

Well our next guest says both are true — that hormonal changes before your period are real. But how you interpret and experience the changes are based on more than just your period—it has to do with culture, and what's happening in your day to day life.

In other words: PMS is not just in your body, or in your head. How we experience it is based on the world around us.

And, as our next guest will tell you, even though millions of people experience PMS every month, scientists do not know much about it.

Joining us now to explore these issues and more is Jane Ussher. Jane is a professor of women’s health psychology at Western Sydney University and she joins us on the line from Sydney.

Jane, thanks for joining us on Hormonal.

Jane Ussher: Pleasure.

Rhea: Let's get started with explaining a PMS a bit. Can you tell us about the kinds of symptoms someone might experience and the spectrum of severity?

Jane: Well, having some sort of changes across the menstrual cycle is completely normal. So, about 95% of women will have some sort of change. So for some women it's negative, so it might be increased irritability. It might be feeling a bit more sad. Some women feel differently about their bodies, they feel more negatively about their bodies. But other women actually feel more energetic, more creative, more sexual. So, there's a whole spectrum of different changes.

For the majority of women it's not a big issue. And women can live with those changes. Some women don't even notice them. But there's a smaller proportion of women, up to around 30%, that might have moderate changes in some months, moderate-negative changes. And it's a very small proportion of women about 5%, who have severe changes that have a really big impact on their lives. And that's primarily the psychological symptoms. So feeling anxious, feeling depressed, feeling that you really can't face the world.

Rhea: And you said about 5% of women experience was that PMS or PME?

Jane: PMDD. OK.

Rhea: PMDD, sorry.

Jane: So I've been doing research on the menstrual cycle and on PMS for over 30 years now, and I'd normally talk about “premenstrual change,” to say these are changes that happen and then normal. PMS is a shorthand for "premenstrual syndrome." And that implies there's something wrong. It's a pathology. It's a diagnosis. And that's really the moderate symptoms which affect up to 30% of women. The most severe symptoms are described as Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder (PMDD). And that's a term that's actually appeared in the DSM, which is the American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic Manual, and that's defined as a psychiatric disorder, it was actually included in that in the DSM in 2013. So that's a very small proportion.

But we need to think about this on a continuum, so if you think most women get some change, about 30% of women. In some months, it's moderate change that might be difficult and a very small proportion of women at the end of the continuum, it's severe change that really needs help and treatment.

Rhea: And to clarify for our listeners what would you say would be the defining line between a diagnosis for PMS and one for PMDD?

Jane: So, it's severity. So if you feel that you can't cope. If you feel you're really out of control. If you feel that you can't face work, you can't face relationships, you might be having suicidal thoughts. That's really on the severe end of the continuum. But if you're just feeling mildly irritated with your partner or with your children or your colleagues at work, that's pretty normal. And it's actually looking at things that you can do in your life to help you cope with that to alleviate stress, to alleviate [the] burden. You'd want to do that across the board, but then in the more normal group, you don't really need to think about medication or anything that's that's going to have a really big sort of medical impact on your body. You're thinking about it normally in terms of, “Okay. I'm feeling a bit more uptight at this time of the month, perhaps I don't take on so much at work, or ask my partner for help or take a bit more time out.” And that generally works for women.

Rhea: OK, so let's try to understand PMS and the cycle a little bit more in detail. Some of these symptoms come from the hormonal changes. So can you break that down for us, how does the change in hormone levels trigger the symptoms of PMS and PMDD?

Jane: Well, that's really the million dollar question. We don't completely know the answer to that. And I think some people have argued that if men had PMS, we would have worked out what was happening from a biomedical perspective many decades, if not centuries, ago and we would have a very good and simple with no side effects cure for it.

Rhea: Right.

Jane: We don't really know and there's many, many different theories so some people say that it's changes in progesterone, some say that it’s changes in estrogen. Other people say it's to do with neurotransmitters particularly serotonin. The answer is we really don't know.

And there's been many, many different forms of medical treatments used, primarily the oral-contraceptive pill in terms of giving women either estrogen or progesterone or combination. Or SSR, so anti-depressants. Prozac being the most common brand name.

Now, what people have often argued is that these treatments work for some women, they don't work for all women, so therefore that's demonstrating that is either an absence of progesterone or an absence of serotonin that's the problem. But if you take a different sort of analogy, if you've got a headache and you take some paracetamol or some aspirin, and it works, that doesn't mean it's an absence of paracetamol or an absence of aspirin that's actually causing the headache. So, often causal interpretations have been made about premenstrual distress on the basis of interventions that can seem to have some effect.

The truth is we really don't know. And what I would say is that we know that there are hormonal and physiological changes happening in a woman's body across the menstrual cycle, so there are hormonal changes, there are potentially changes in neurotransmitters. There's also changes in physiological arousal, so in autonomic arousal, so women can feel more “on edge,” but they can also feel more excited, they can feel more sexual. And those changes actually interact with what's happening in a woman's life.

So, if you're under a lot of stress, if you're under a lot of pressure, if you've got lots of difficulties in your relationship, you’re juggling work and life and children and trying to have a social life, trying to stay slim, you know, a lot of the pressures that any woman's under -- that actually can be more acute and can actually make you feel more sensitive, more vulnerable in the premenstrual phase of the cycle. And then what you think about those changes also has an impact. So if you think, "Oh, I can't cope. Oh, I'm crap. Oh, I'm fat," because you feel a bit bloated, that makes you feel worse. So it's a vicious cycle. So, what we need to look at is the biological factors what's happening in the body alongside a woman's environment and alongside what she's thinking about what's happening to her. And that's where we can help women in non-pharmacological ways, by unpicking some of that cycle.

Rhea: Now, I find that really interesting because you've also written that PMS is a Western cultural concept. So keeping in mind that women experience PMS very differently across the world or that they may report on experiencing PMS differently across the world, can you explain for our Hormonal listeners, how this actually works or how you found this out?

Jane: Well, if you take a step back, what we know is that symptoms and illnesses are always culturally located. So, if you go to different cultures, different points in history, we have different, what people describe as symptom complexes. What we see as legitimate illnesses and ways that we actually report distress.

So, if you go back to PMS and reproduction, in the 19th century there was no concept of PMS. In fact it was first discussed in 1931, in North America. And in the 19th century, women reported "hysteria," and then “neurasthenia.” And these were "disorders," I put inverted commas, that were often associated with the reproductive system. You know, we can go back as far as Plato and Hypocrates and they believed in the wandering womb, and that was seen as the problem in women's bodies.

In 1931, [Robert] Frank, who was a medical doctor and also Karen Horney, who was a psychoanalyst, first described this notion of what they talked about as premenstrual tension, PMT. And they actually said it was to do with hormones, to do with estrogen. And PMS was first described in 1956 by Katrina Dalton who is a British gynecologist.

Now, these notions that women would have psychological disturbance in the premenstrual phase of the cycle were happening in the U.K. and in the U.S. They really had very little impact in other parts of the world. And you really see this legacy today. Whereas in the U.S., the U.K., and in Australia, we've taken up this pathologizing discourse, as I would call it, around the menstrual cycle and around the premenstrual phase of the cycle. And we expect women to be mad or bad or dangerous premenstrually. And women take that up, in hundreds of thousands and actually feel irritable, feel angry, and then blame it on them, on their bodies on the menstrual cycles.

Now what we know in terms of other cultural contexts, if we say to women: “Do you experience those sorts of changes across the cycle?” women don't report them. They may report some physical changes, so they may report feelings of bloating or sometimes menstrual pain. But that usually is when the period starts. But they don't tend to report premenstrual symptoms, particularly in Asian cultures. And what we also know is that when women come from cultures where there isn't a discourse around PMS and they move to the U.K. or the U.S., then they start to report it.

So the argument is that it's a culture bound syndrome. It's both a gendered syndrome, because it's a way of attributing women's anger and distress to their bodies, but it's also a culture bound syndrome because it's been created by Western, particularly North American and British culture and then women take that up.

Now what's interesting about it is that women actually experience anger, depression, distress, classic symptoms of PMS and PMDD across the whole cycle. But what we know is that when they're premenstrual, they'll attribute it to their bodies but when they're [at] other times of the cycle they’ll attribute it to other things in their life. So they might say, "Oh it's my partner or I'm late for work or you know it's Monday morning and I'm feeling lousy." So even within Western culture, we can see the way women are actually inculcated in what some might say in a negative discourse around menstruation.

Rhea: That's the part of your research that I find most interesting, that you find that people who menstruate, their symptoms or their changes are not strictly hormonal. Could you tell me a little bit more about what you mean by that?

Jane: Well, it's not simply a hormonal cause for any negative experiences that people who menstruate might have in the premenstrual phase of the cycle.

So, I've been involved in developing psychological support for women who experience moderate to severe PMS and PMDD. And we've developed a form of therapy, psychological therapy, that we've evaluated both on a one-to-one basis as a self-help therapy and as a couple therapy. And what we've found is, we've interviewed hundreds and hundreds of women as part of these evaluations, and often I say to women, you know, “Tell me about your PMS.” And the first thing they usually talk about is an argument or something that's happened with their partner or with their children, sometimes at work as well, but, generally women control it at work.

So what's happening is there's a trigger. There's an environmental trigger that's happening and I'll just give you a classic example from one of our interviewees. But this is a really typical example of PMS. I said to a woman in one interview, “Tell me about your PMS.” Now, she didn't talk about hormones, her body, what was happening inside. She said, "Well, I was standing at the kitchen sink and I was doing the dishes, and I had the dinner on the stove for the two children and the children were arguing, and I was trying to get them to do their homework and I was looking out in the garden and my husband was sitting there having a beer.” And that was her PMS. She was feeling really, really angry with her partner and she yelled at him something. And then she felt really bad about herself and she said, “That's just typical PMS to me.”

Now, I would say that that's actually more about what's going on between her and her partner than what's happening hormonally in her body. And it might be that in the premenstrual phase of the cycle, she's less likely to self silence and more likely to be cranky with him. But actually, what's useful to do is take a step back and think, well maybe, she shouldn't be doing all of those things while someone else who lives in the houses is having a nice time, having a beer. Maybe it's about asking for support. Maybe it's again about getting her partner on board. And in fact what we found is in relationships where women have that support, where they can say, “Look I'm feeling a bit irritable today,” or “I feel like a bit need a bit more help today, or “Can you take the kids today?” they're less likely to experience premenstrual distress. So it's certainly not just hormonal.

[Sponsor Break]

Announcer: Hormonal is brought to you by Clue. The period tracking app, and menstrual health resource, that takes all parts of your cycle seriously.

Jesse: Well, I think a lot of Clue users don't realize that the website is basically an encyclopedia.

Announcer: That’s Jesse. He’s an engineer who works on the website. He says anything you can track on the app, you can also read about online.

Jesse: The really important work that we're doing on the website is getting accurate, reliable, and empathetic health information out to people for free. And it's really cool, it’s really important work. And I think part of why it's so important is that there are a lot of websites that provide sort of related information but it's often very clinical sounding and a bit intimidating. And so this is all written from a point of view of empathy and care, but it's also scientifically backed.

Announcer: To support the science-backed app and website that you know and love, subscribe to Clue Plus. It funds the work here at Clue, the period tracking app that doesn't sell your data, doesn't show you a bunch of ads, and was founded and is led by women.

For more -- check out Clue.Plus.

Alright, back to the show.

[End of Sponsor Break]

Rhea: Right. I can completely understand that because actually once I got into a long term relationship in my early 20s, it was the first time I actually felt comfortable enough to start talking to my romantic partner and saying listen, "I'm not having a very good time this week. It's time for you to just like give me some alone space, alone time, where I can just indulge in my own, in myself.” Basically. And it began this sort of journey of like self care and taking time out.

So, instead of looking at this one week every month as this really terrible thing that's about to happen to me, I started to turn that narrative around a little bit and make sure I let the people closest to me in my life know, "Listen this week it's all about me taking care of myself." So I know, like I've done that for myself and it's been really helpful.

I was wondering if you could tell our listeners how their partner, or how the close people in their lives, in their families, can actually help or affect the way that they experience any type of menstrual change.

Jane: Well. I think the key to it is communication. And you've given a really good example from your own life.

So a number of things. I think the first thing, as a woman yourself, to be aware of what's happening. So if there are particular times where you feel more vulnerable, you feel like you do need more space, and actually when I talk to women and I say, "What's this thing you do to cope with PMS?” They say, “I go under the dune or under the duvet," or you know just the classic -- you know Virginia Woolf talked about “a room of one's own.” And it doesn't have to be literally a room, it can be some space that can be going for a walk, going in the bath, just saying you know I just need some me time. And even if that's only for half an hour that's really important for women. So having an awareness of the changes in our bodies, those changes may not happen in the premenstrual phase of the cycle, some women actually feel distressed in the luteal phase.

Some people, some women feel very distressed during the menstrual phase when they're bleeding and actually if you track your cycle then you can see when you’re actually up and when you're down and actually understand your own pattern. So awareness is really important. The second thing is actually communicating with your partner or partners if you have more than one partner or it might be if you're living with friends or living with family, what you need and when.

So I say one of the things is don't let things build up until that premenstrual phase where you're actually going to blow a gasket and get really angry. Talk about things you're not happy with at other times when you might be feeling a little bit more calm. Actually say, “Look. I'm not happy with the fact that you don't ever help with the kids” or, “I'm not happy with the fact that you always leave your towel on the floor.” Those are very stereotypical examples I'm coming out with here. Or, “I'm not happy with the fact you don't listen to me when I'm trying to tell you something,” and actually see if you can work that out at other times in the cycle.

But if you are feeling vulnerable and everything's too much, it's actually about kind of saying what you want: Can I have a cuddle? Can you leave me alone? Can I have some space? Can we go out and party? You know actually communicate that to your partner.

Now what we can't guarante is that your partner is going to listen and we've done research in both heterosexual and lesbian relationships and we found that some men are incredibly supportive but men are actually less likely to be supportive of women. We could say it's because they don't empathize. They don't understand. Whereas if you've got a woman partner, she's more likely to go through some sort of changes herself so she's more likely to understand.

It's also we know in lesbian relationships, they tend to be more egalitarian. So women are more likely to be sharing things in the house. But that's the case also in a lot of heterosexual relationships today. So, I think women need, if your partner is a man, then you need to explain what's happening. Help the men to understand. That can actually then get the partner on board for support.

Rhea: Right. So tell me a little bit more about the study that you wrote about where you found that people in lesbian identified relationships actually report having less severe PMS. Could you tell us some more about that?

Jane: Well, what we found was that women in heterosexual and lesbian relationships experience premenstrual change across the board. So it's not that lesbians are immune to PMS so they might have the same sort of symptoms they might feel irritable, they might feel distressed, they might feel more vulnerable. But it's actually what happens in terms of the spiraling.

What we found is in heterosexual relationships for some women, the partners would provoke them when they were premenstrual, so they would pick a fight. They would insult them said one woman talk to us about her partner saying, "Are you schizo Elaine? Or Mad Elaine? or Bitchy Elaine? What have I got today?" Which actually made her feel really distressed. The often male partners would avoid women, just saying, "I can't be with you when you're like this," would be very blaming and quite negative. And in fact there's a whole website, where men talk about the terrible experience they have of living with premenstrual women. And so that can actually, that sort of ties into a general cultural stereotypes about, you know, “mad premenstrual women,” and how they, really what I've called the “monstrous feminine incarnate.”

So, that was much more common in heterosexual relationships. And what we found in lesbian relationships is the partners, there was no examples of partners doing this pathologizing, of making women feel mad, making them feel worse. So, a woman might be irritable with her partner. But, the partner was much more likely to say, "Look. I think you need a bit of space and I'll help you out do you want to have a bath? Can I make dinner tonight?” And actually to be able to empathize with the experience. And also that women were less likely to get to that peak of anger and irritability, because they were getting more support at home and that is a real key to to women's premenstrual distress, is that sense of over responsibility of having to do everything never having time for themselves.

And so in the lesbian relationships, women were more likely to have that support, so less likely to get to that kind of extreme of distress. So, I think that's what's really important to be able to both communicate about changes and about what you need but also to look at general issues in a relationship that might be causing distress. And having unequal distribution of labor is a really big cause of anger in many, many women's lives.

You know, I've heard it said that men complain that they want more sex and women complain that they want men doing more housework. And actually if men did a bit more housework with the women partners, maybe there'd be less anger in the relationship and more sex, so there'd be a bit, everybody would be happy all round.

Rhea: That would be a dream. I'm just thinking about the lesbian identifying couples where that partner’s also leaving their towel on the bathroom floor. I think that that could probably lead to a spiral as well.

Jane: And if you’ve got both women who are premenstrual at the same time… So, I'm certainly not saying there's a lesbian utopia out there and that women in lesbian relationships don't have fights because I certainly do. But I think having empathy can help.

Rhea: All right. So communication for sure. You said tracking your cycle -- so of course being aware of which parts of a person's cycle or your own cycle that you may feel or have characteristic traits of feeling a certain way. I know that that has really helped me, tracking, the communication, as you said before. And then of course the empathy and having let's say a more egalitarian relationship.

So what would be, let's say your prescription, beyond those four tips for the folks or for the cultures, that are struggling with premenstrual syndrome or menstrual changes?

Jane: Well, I think the first thing is keeping a diary so that you know what's happening, so you learn your own body and you learn your own cycle. And we know that that's actually one of the best ways of reducing PMS, and in fact, it's a frustration for many PMS researchers because women say, "Oh I get terrible PMS,” and then you have to get them to keep a diary for three months and it can kill the PMS. So, it can be as simple as that.

The second thing is actually looking at, in part of your diary look at, what other things are happening in your life, when you have days that are bad. So, look at the triggers and that can help you see whether it's things at home, whether it's things at work. Keep a diary of your feelings as well, so what sort of things are you saying to yourself? What sort of thoughts are you having? And are you having very negative self thoughts, and you can challenge those so if you think, "Oh, I can't cope, I feel terrible, I'm awful, I'm ugly" and they're things that women often say or women experience severe premenstrual distress or moderate pre-menstrual distress. So challenge those thoughts. Look for alternative evidence. Rather than thinking, “I can't cope," just thinking, "Well, I need an easier day today. I've got too much on." And legitimate taking time for yourself.

So, it's the other thing leading to that is about self care and coping and you've already talked about [yourself] in terms of your own life. But it's actually one of the things we do when we work with women therapeutically is we say to them: “Think about some things you enjoy doing and actually make sure you do at least one of those things every day.” And a lot of women surprisingly don't do anything that they enjoy. Particularly, if they've got children and they're working and there’s just no space in their lives for things that they enjoy. Actually taking things time for things you enjoy even if it's just half an hour a day, actually having some space away from responsibility, so that sort of self care that we need to do, looking after ourselves physically and psychologically.

And it's about not feeling as if you're going mad. Some of the women we've talked to say, "Look I think people say it's all in your mind, it doesn't exist. I feel like I'm going mad." Actually thinking, No, there are some changes happening in our bodies, but what's happening in our lives and what we think about them, all combines together to result in this PMS or Premenstrual distress.

And we can intervene by looking at challenging our negative thoughts and looking at what's happening in our environment. And that will significantly reduce the premenstrual distress.

Rhea: Are there cultures who view premenstrual change as a sort of superpower or being super charged, a supercharged time of the month?

Jane: Well, in some cultures, menstruation is just seen as a normal part of life. And the premenstrual phase is just accepted as a normal part of life. But what we see with some women, if you ask them the question about positive premenstrual change, or do you get any positive experiences? What you find is that some women will talk about having much higher libido, that it is a time when women really want to have sex.

It's also for some women, for example who are athletes, they can feel that they've got much more energy. Women who are writers can feel much more creative. Artists feel much more creative. I know myself, at times, when I was premenstrual, I often found it was the best time to write and when I was writing books, I'd often have an incredibly creative time.

If we think about it as an increased energy, it can actually be channeled positively, as well as negatively. And we have a sort of cultural context where we expect it to be seen as anger, as irritability. But women can actually turn that around and actually channel it really positively.

I think it's really interesting, also, to look at menstrual art. There's been a resurgence in menstrual art, which sort of reflects those sorts of ideas, where we're in a way, it's a counter narrative to this seeing as menstruation and the premenstrual phase as a sign of a monstrous, is actually celebrating the power of menstruation the power of that premenstrual energy. And I think that's something that women can tap into and certainly enjoy.

Rhea: I also found in reading your research and reading your articles, you found that women in Asia and Latin America tended to report that they did not have some sort of premenstrual change. Do you have any idea why that may be?

Jane: Well there's different arguments for it. What I would say is that we don't have that notion within particular cultures that the premenstrual phase is a sign of illness. So women are not then, if they feel any psychological changes at that time, they're not attributing it to their bodies. So that they don't have an expectation that they will have any psychological symptoms. And so that's, I would say, that's the primary reason why. It's not that women in Latin America countries or Asian countries have anything different happening physiologically. It's just that there's not that whole expectation that they will experience premenstrual change.

Now, some people could say that means, “Oh my God, they've got PMS and there's just no legitimate syndrome.” And there maybe a little bit of that. We've done some research here in Australia, where we've interviewed women from migrant and refugee backgrounds and we asked them about PMS and premenstrual change, and they all laugh about it, and they say, "Oh no. There isn't such a thing," they don't have it.

But then when we say to them, "Do you ever feel more irritable at that time?" And some women will say, "Oh yeah, when I think about it, I do sometimes. But it's not a big deal." And they think it's kind of ridiculous that you'd give it a label and that you'd certainly want treatment for it.

So it may be that there's some change in women's experience but they're not, they're not seeing it is a really negative thing. It's not a really big deal. And they certainly don't either self diagnose or feel that they need a diagnostic label for it. Now, there may be some women in those cultures who do get severe changes and we don't understand why some women are at the end of the continuum with the severe changes and in those cultures, those women may not be getting the help that they need. So that's a downside of not having this cultural discourse around PMS.

Rhea: Jane, this has been a fascinating conversation. Thank you so much for joining us.

Jane: It's been a pleasure.

Rhea: Jane Ussher is a professor of Women's Health Psychology at Western Sydney University. You can read more of her work in her book: "The Madness of Women: Myth and Experience.”

Hormonal is brought to you by Clue. If you like the podcast, subscribe and rate us five stars on your platform of choice. Or find us on social media!

To support the work here at Clue -- subscribe to Clue Plus. Every cent goes towards informing you -- that includes the app and the archives of meticulous menstrual health information on the website. Including the answers to the question at the top of the show. Check the links in the show notes for more.

You can find out more about Clue Plus at Clue.Plus.