Illustration by Marta Pucci

What you may not know about ovulation: common questions and misconceptions

The monthly release of an egg from the ovary is a fascinating process. It’s often something people first learn about when they are trying to get pregnant. But learning about ovulation can help you even if you aren’t trying to conceive. Ovulation affects your body and brain in ways you might not have imagined.

First, read Ovulation 101 to get the basics of ovulation. After you have a handle on how it all works, you can dive into common questions and misconceptions — which we’ll address here.

Can you ovulate twice in one cycle?

No. Only one ovulation can happen per cycle. You can, however, ovulate two (or more) eggs at the same time. When this happens, there is the potential to conceive fraternal (non-identical) twins if both eggs are fertilized. But having two separate eggs released at different times within the same cycle doesn’t happen.

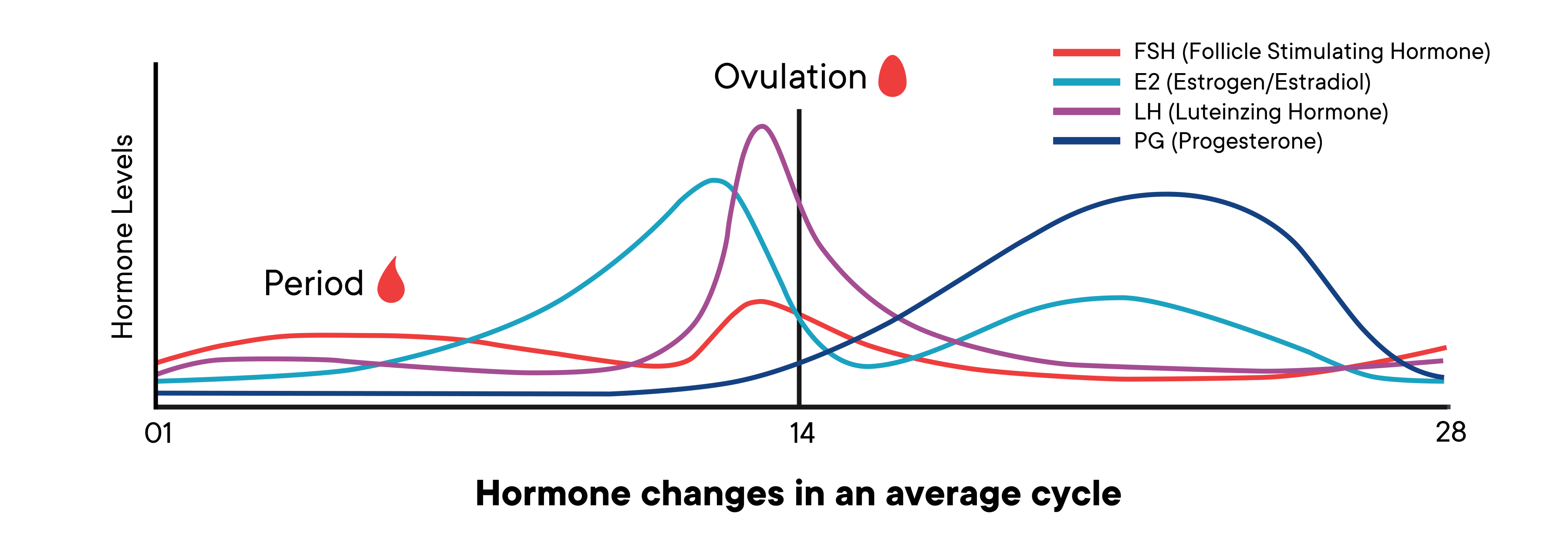

Once you have ovulated, your empty follicle turns into something called a corpus luteum. The corpus luteum is responsible for making sure another ovulation doesn’t happen (among other things). It starts pumping out progesterone, as well as some estrogen and a hormone called inhibin. The concentration of these three hormones provides negative feedback to the hypo-pituitary axis (HPA), which inhibits the release of three other hormones: gonadal stimulating hormone (GnRH), follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), and luteinizing hormone (LH). By suppressing the release of those hormones, follicles will not develop to the point of being ready to release an egg (1).

Can taking prescription NSAIDs (painkillers like aspirin or ibuprofen) stop you from ovulating?

NSAIDs (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) are a group of medications used for treating pain, reducing fever, and reducing inflammation. NSAIDs are often used to treat headaches, colds, menstrual cramps, and arthritis. NSAIDs have many different names and types, some common NSAIDs being aspirin and ibuprofen.

These medications work by stopping the action of a group of enzymes called cycloxygenase 1 and 2 (COX-1 and COX-2) (2). These particular enzymes are related to ovulation because they are involved in producing prostaglandins (the same hormone-like compounds responsible for bringing on your period). During ovulation, prostaglandins are also involved in the inflammatory response needed for your follicle to release an egg. If the follicle does not release the egg, then ovulation cannot occur (2).

In 2015, a study announced a dramatic decrease in ovulation in women taking NSAIDs at doses that would require prescriptions in most cases (3). In this research, 39 women of childbearing age who suffered from back pain were given a course of one of three different NSAIDs treatments starting on day 10 of their menstrual cycle (this is in the follicular phase, before ovulation happens) (3,4).

The NSAID medications used in this study were diclofenac (100mg daily), naproxen (500mg twice daily), etoricoxib 90mg daily. In most countries, these medications and doses would need to be prescribed by a healthcare provider in order to treat pain, particularly chronic pain. While these NSAIDs are in the same family, the results of the study should not be compared to the effects of taking a single over the counter ibuprofen every so often. These are prescription strength medicines with strong contraindications (like during pregnancy, ulcers, or liver disease) and side effects such as (but not limited to) increased cardiovascular thrombotic events and gastrointestinal bleeding (5,6,7).

After 10 consecutive days of NSAID treatment, the hormones and follicle health of those studied were assessed. Many of the women taking the NSAID therapies didn’t ovulate — they did not release an egg, in comparison to the women taking a placebo pill (3). When the NSAIDs were removed, the effects reversed, and ovulation occurred normally the next month (3,4).

Other researchers have also noted these results in mice and rabbits since the 1980s (2). Another recent study focusing on fertility and NSAIDs users found that women with rheumatoid arthritis taking NSAIDs were more likely to have unexplained delays getting pregnant, in comparison to people with RA who were not using NSAIDs. This data also suggests that there is some link between conception and NSAID use (8).

Scientists suspect this research could have potential uses for emergency contraception in the future too. More research is needed here (4).

Can we regenerate our eggs? Is it possible that new eggs are created after we’re born?

The commonly held scientific dogma regarding the female biological clock is that women are born with all the eggs they will ever have. These slowly expire as we move from birth until menopause — with a very few lucky eggs getting released during ovulation. This notion, however, has been challenged by researchers over the past decade.

Back in 2004, a series of experiments demonstrated an inconsistency between the number of oocytes (immature egg cells) available in a mouse’s ovaries at birth, in comparison to the amount of follicle (developing egg cells) breakdown happening throughout the mouse’s life. There was a mathematical imbalance — more follicles were dying than were originally available at birth. This suggested that oocyte cells were being regenerating after birth (9).

Another study showed germline cells (cells that can generate new eggs) in human ovaries could be identified and extracted. These extracted germline cells could generate new eggs cells in a lab, and could also generate immature egg cells when injected into female human ovary tissue grafted into a lab mouse (10).

As of yet, no human births or conceptions have been attributed directly to these germline cells, but other advances in fertility treatments are being made. Scientists are injecting mitochondria from these cells into older egg cells, to promote increased cell energy production, which has helped increase fertility rates up to 30% (11).

A study from 2016 also further demonstrated the regenerability of germcells in human ovaries, in subjects being treated with cancer medications for Hodgkin lymphoma. Participants taking this particular chemotherapeutic cocktail were found to have a higher follicle density (more follicles) in their ovaries than participants not taking these medications. When these chemotherapy treated preliminary follicles were sampled from the ovaries, they did not develop as well in the lab setting in comparison to cells from untreated ovaries (12).

These new breakthroughs in research are still very much in their infancy. There have been many critiques, challenges, and problems with reproducibility of these experiments about regenerative germline cells; more research is needed.

Download Clue to track when you are ovulating.