Illustration by Emma Günther

A short history of modern menstrual products

How did we end up with the tampons and pads we all know?

For most of human history, menstruation has been associated with taboos and stigma. Even as modern menstrual technologies began to develop, beliefs about menstruation being unhygienic and discussions of these concerns “unbecoming” kept menstrual products out of the mainstream. Before 1985, the word “period” (to mean menstruation) had never been uttered on American television. However, these cultural norms did not stop technological innovation: the first disposable pads hit the market in 1896. Today, menstrual products are a multi-billion dollar worldwide industry, with prime-time ads and countless products on the market.

How did we move from bandages and plant fibers to menstrual cups and modern tampons (1)? And as period technologies improve, what have they changed for the people who use them?

(If you're wondering how people around the world managed their periods before the 1800s, read our interview with historian Helen King here.)

1800s to 1900: Turn of the century – From rags to riches?

In European and North American societies through most of the 1800s, homemade menstrual cloths made out of flannel or woven fabric were the norm–think “on the rag.”

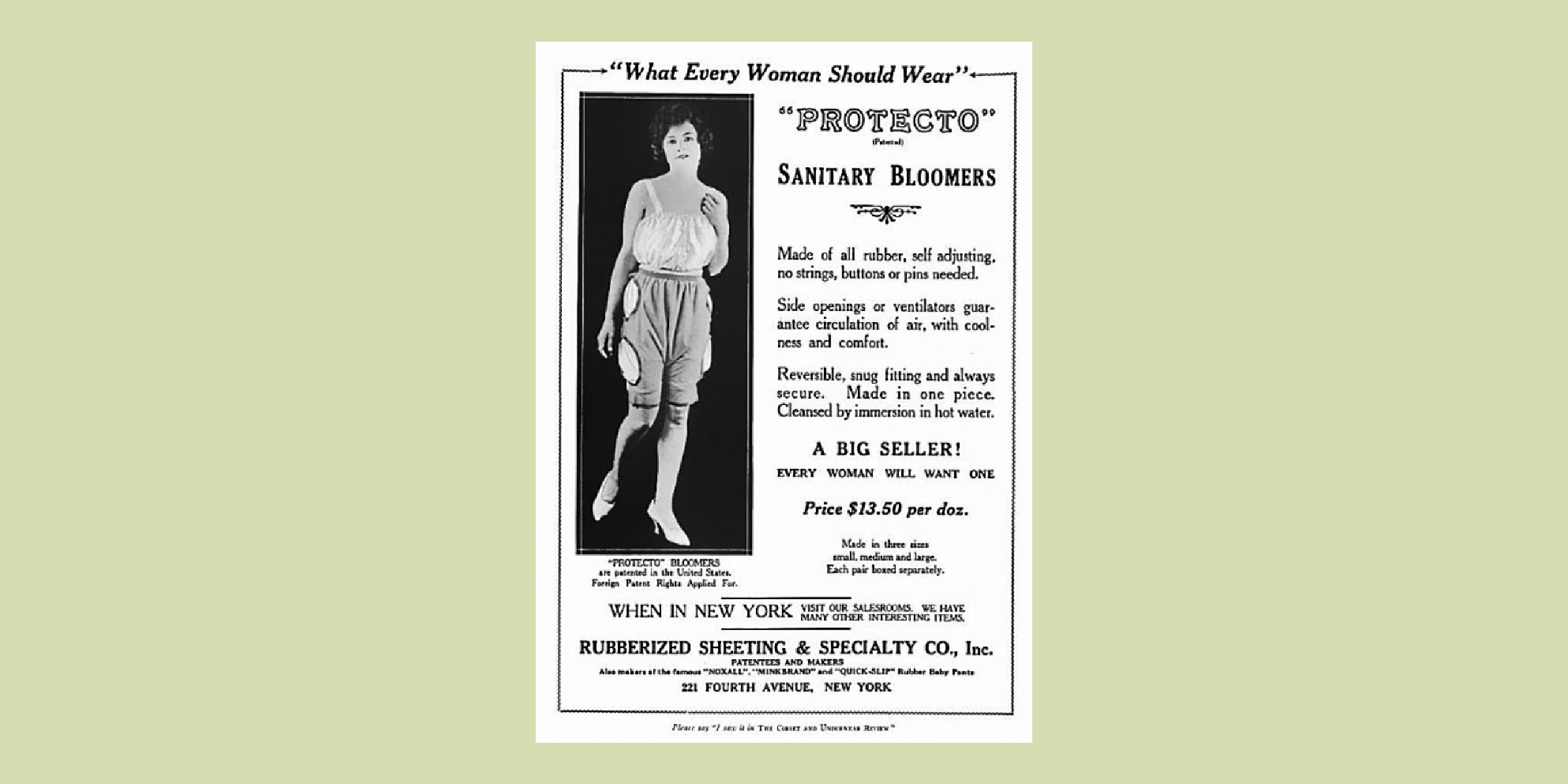

By the turn of the century, concerns about bacterial growth from inadequate cleaning of reusable products between wears created a new menstrual “hygiene” market. Between 1854 and 1915, twenty patents were taken out for menstrual products, including the first menstrual cups (generally made of aluminum or hard rubber), rubber pants (literally bloomers or underwear lined with rubber), and Lister’s towels (a precursor to maxi pads) (3).

Period pants made of rubber (3).

While products were marketed door-to-door by the 1870s, the first commercial products available for a mainstream audience came in the 1890s with the products appearing in catalogues. Menstrual tools including a “Ladies Elastic Doily Belt” (a silk and elastic belt to which you’d attach a pad) and “Antiseptic and Absorbent Pad” were introduced at around the same time (2).

In the 1890s, new tools like the Ladies Elastic Doily Belt started to appear in catalogues. You'd attach the pad to the silk and elastic belt (2).

But while inventors were beginning to see the need for these products, moral taboos around menstruation meant consumers were still hesitant to be seen purchasing them. Case in point: the commercial failure of Lister Towels, the first disposal pad made of gauze and cotton, which first hit the market in 1896 (2).

1900s to WWI: Lessons from the battlefield

During the First World War, nurses noticed that cellulose was much more effective at absorbing blood compared to cloth bandages. This inspired the first cellulose Kotex sanitary napkin, made from surplus high-absorption war bandages, which was first sold in 1918.

By 1921, Kotex had become the first successfully mass-marketed sanitary napkin (3, 1). In addition to providing the innovation for a product that would drastically change the options available to women, the war caused another major shift in women’s lives: they were now needed to contribute to factory production in a way they had never been before. Through ads and bathroom redesign, factory employers during WWII encouraged women to use menstrual products in order to “toughen up” and continue to work during their monthly bleeding. (This was in spite of the pervasive questioning of women’s “emotional stability” – female pilots were encouraged not to work during “that time of the month”).

The beginning of mainstreaming period products meant women could take more control of their autonomy, allowing them to work and participate in activities outside of the home in a way they hadn’t been able to before (3).

1930s to 1940s: “The Kotex Age” – Appealing to the mainstream

While homemade menstrual rags were still in use throughout Europe until the 1940s, the 1930s brought a surge of ingenuity in period product offerings (1). Modern disposable tampons were patented in 1933 under the name “Tampax.”

Due to hygiene concerns about to the proximity of pads to fecal bacteria, tampons were generally concerned a healthier alternative by the medical community (4). Dr. Mary Barton, an English physician at the time, agreed in a correspondence published in the British Medical Journal in 1942 (11). She began the article: “As a woman and a doctor I feel that I cannot allow the correspondence on this subject to pass without comment.” (pp 709). She addressed concerns that tampons would be “unbecoming,” and pointed out that tampons did not cause abrasions and boils on the vulva as sanitary pads had for many of her patients. She conceded that leaving them in for too long could lead to infection (11).

Medical and marketing interviews found that most women did not return to pads once they had learned how to insert tampons correctly. But many communities were hesitant to embrace tampons because of moral concerns about virginity, masturbation, and its potential to act as contraception (1). Dr. Barton included this in her report, mentioning that healthcare practitioners should take note of individual’s personal concerns regarding potential to rupture the hymen (11). That being said, she was a strong supporter of increased options for women, stating:

“We surely do not retain our femininity at the cost of inability to make the menstrual period as comfortable and unobvious a process as possible. I believe that femininity is an attitude of mind which is consistent with knowledge and experience, and should refuse only those ‘improvements’ that encroach upon our receptiveness or frustrate our attempts to promote health and happiness” (11).

But because people continued to be hesitant about tampons, innovations in pads continued to bloom. Mary Beatrice Davidson Kenner, a female African-American inventor, patented the sanitary belt in 1956, the first product featuring an adhesive to keep the pad in place (5).

In 1927, Johnson & Johnson hired pioneering psychologist Lillian Gilbreth, to conduct a study on merchandising the sanitary napkin (6). She interviewed thousands of women across the country, answering questions about size and fit (they tended to be too large with inflexible edges) and preferences (most women wanted smaller, more discreet packaging). She inspired a new wave of very successful ad campaigns focused on allowing girls to maintain their innocence, so to speak, by separating menstruation from sex and reproduction. Ads presented period products as allowing girls to participate in sports and recreational activities, helping to reinforce the idea of adolescent girls as playful youth (3). This strategy was also used by tampon campaigns hoping to overcome the moral concerns people still had about them.

1950s – 1990s: Entering the modern age – Tragedy, activism & regulation

Creative modifications to period products continued into the age of peace, love, and rock and roll. The first beltless pads came out in 1972, inspiring variations like heavy flow, light flow, and mini-pads. In the 1980s, versions of modern maxi pads and pads with wings hit the market.

Tampons continued to increase in popularity. But a massive health concern about them made news when over 5,000 cases of Toxic Shock Syndrome (TSS) were reported between 1979 and 1996 (7). Most of the cases were linked to a specific tampon brand and specific materials which are now no longer on the market. While these health scares did not discourage women from using the products, they brought to light a lack of government regulation over the safety and composition of menstrual products. This lead to more focus on more “natural” alternatives.

In 1956, Leona Chalmers updated the menstrual cup, using softer materials to make a product more like what we use today (5).

The first menstrual cups were made of aluminum or hard rubber; now, they are typically made of silicone (2).

Some more extreme options were presented, including a powder that could be inserted into the vagina, which was meant to neutralize the pH of period blood and prevent bacterial growth (3). While these more creative measures didn’t take off, reusable menstrual cups, period sponges, and biodegradable options became more popular throughout the 1970s as second-wave feminist and environmentalist movements grew (3). Mini-pads were a huge success when they hit the market, even inspiring fan letters from women who finally felt comfortable (1).

As the feminist movement pushed women to become comfortable with their bodies, free bleeding was adopted by women who resented the fact that they were expected to hide and feel ashamed of their periods (though it was hardly mainstream) (3).

The most revolutionary development in period management came in 1971, when a women’s self-help clinic introduced the “extraction method” (3). This invention came out of research on safe abortions (8). Women used a suction device to evacuate all the contents of the uterus, shortening periods from around 5 days to just a few minutes. The procedure was seen as a blessing for athletes and people with especially painful periods, and the inventors patented safer and more effective tools throughout the 1970s (5). In spite of the benefits, research into the safety of this procedure was restricted, partly because of its association with early abortions (5). The method required a doctor to perform the procedure, making it potentially costly (3). This plus the lack of medical data investigating potential long-term effects prevented it from becoming mainstream.

2000s to present: Where are we now?

Today there are a plethora of options for managing periods, from period panties to menstrual cups, organic pads and tampons, and, of course, the still-prevalent standard tampons and maxi-pads. As of 2000, over 80% of women used tampons, with pads and panty liners close behind (9). Even the cloth options from the 1800s are making an updated comeback, with more and more options for anti-microbial period panties hitting the market.

As concern about the environmental impact of disposable products grows, many are returning to reusable organic methods, like the menstrual sea sponge and silicone cups (though both have been associated with cases of TSS (10, 12, 13). As people with periods learn more about our options, we are able to take our health into our own hands, making the best decisions for our own bodies and lives. While women have always been intimately involved with the development of period products, female entrepreneurship continues to grow in this market.

Products and ad campaigns are also shifting to focus more on all bodies that get periods, including trans men and gender non-binary people.

From early on, the expectation (ironically) was that by hiding their menstruation, women were seen as more feminine, hygienic, and capable. Strategies based on fear of “discovery” continue to be employed by marketers today, from odorized products to silent and discreet packaging. But these ads have also shifted towards a more feminist message, portraying tampons as liberating, allowing women to take control of their bodies and participate in areas of society that didn’t welcome them before (3).

History shows us that advances in menstrual technologies have had significant impacts on women’s health and personal and professional freedoms. From patents to pilots, menstrual technologies have been opening doors for women and people with cycles throughout history.